Datsueba: A Buddhist metaphore

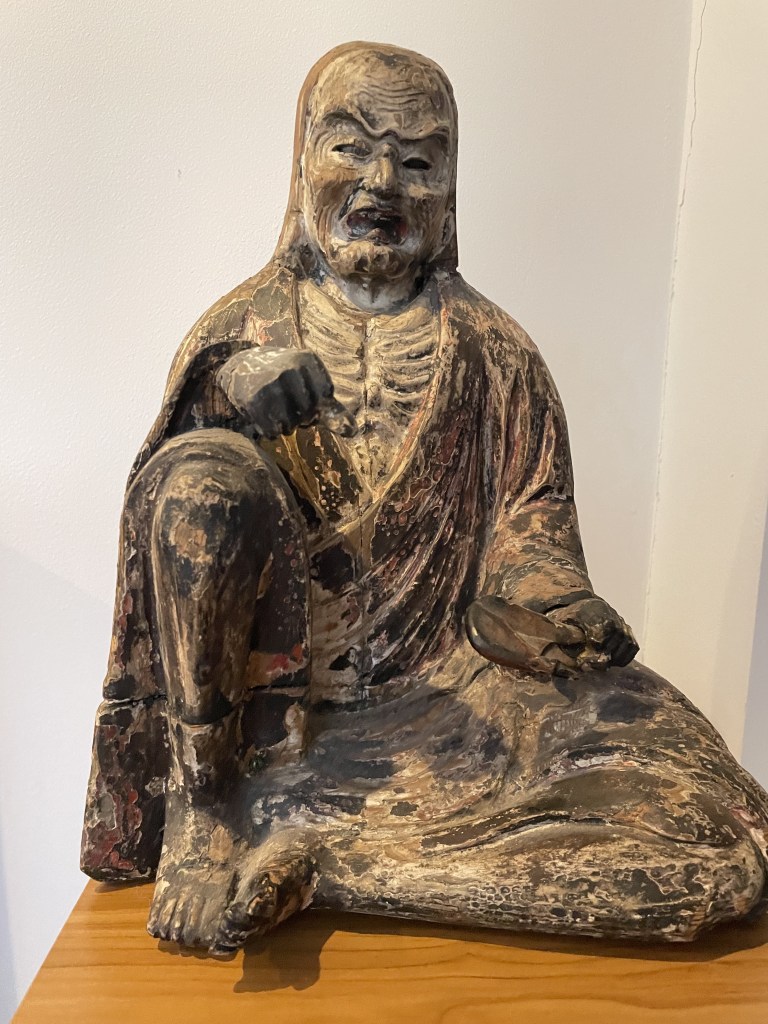

I am very lucky to posses this ancient wooden statue of a Buddhist saint/god Datsueba:

Datsueba, also known as the “Clothes-Snatching Old Hag,” is a complex and multi-faceted figure in Japanese religious tradition. Her portrayal transcends a single role, evolving over centuries as she became a central figure in the spiritual and cultural imagination of Japan. Representing the liminal space between life and death, Datsueba serves as a gatekeeper to the afterlife, a harsh yet compassionate presence whose essence is expressed in many Buddhist and shamanic beliefs.

The Origins and Early Depictions

The earliest textual reference to a figure resembling Datsueba can be found in the story of “Renshū Hōshi” within the Dai Nippon Koku Hokekyō Genki (commonly known as the Hokke Genki), composed by the Tendai monk Chingen between 1040 and 1044. This collection of tales highlights the miraculous power of the Lotus Sutra, and in one such story, Datsueba marks the boundary between the living and the dead. She is portrayed not only as a punisher but as a being who submits to the power of the Lotus Sutra, underscoring her dual role as both a figure of judgment and a symbol of the sutra’s salvific power.

Datsueba’s sculptural representation emerged later, with one of the earliest known wooden statues dating back to 1375. This figure, enshrined at the Ashikuraji Enma Hall in present-day Toyama Prefecture, depicts Datsueba in a posture of introspection, her gaunt form and exposed ribs emphasizing her connection to mortality and the transience of life. Though damaged by fire in 1782, the statue retains many traditional features, such as a raised knee and the remnants of her signature attributes.

Her Role and Evolution in Ritual and Lore

Datsueba’s primary function in Buddhist texts and folklore is to strip the clothes from the deceased as they enter the underworld. This act symbolizes the removal of earthly attachments and the soul’s preparation for judgment. However, her role extends beyond this initial depiction. In narratives like The Story of the Revival at Chōhōji, Datsueba appears as a suffering being, a manifestation of Dainichi Buddha, or even a benevolent figure who provides clothes at birth, creating a striking duality between her roles in life and death.

Over time, particularly during the Edo period (1603–1868), Datsueba gained prominence in independent worship. Devotees began venerating her as a unique deity, distinct from the Ten Kings of Hell or Jizō Bosatsu. Regional cults emerged, each interpreting her essence through local traditions, rituals, and beliefs. These diverse practices transformed Datsueba into a figure embodying maternal care and protection, even associating her with childbirth and child-rearing—roles absent from her original characterization.

Mystical Attributes and Symbolism

Datsueba’s attributes carry profound symbolic weight. She is often depicted holding a strip of cloth as we can see here in her left hand, representing her act of taking garments from the dead. However, in devotional practices, this cloth transcends its literal meaning, becoming a symbol of salvation and spiritual transformation. In some traditions, the cloth is imbued with protective and purifying qualities, reflecting her dual nature as both a harsh examiner and a compassionate guide.

Her skeletal form, with exposed ribs and a gaunt face, serves as a reminder of the impermanence of life and the inevitability of death. Yet, her role is not solely one of judgment. In certain tales, as pointed out she helps highlight the power of Buddhist texts as a refuge, particularly the Lotus Sutra, and even becomes a symbol of rebirth and renewal.

The Eight Immortals Connection

Datsueba is often linked to Lü Dongbin, one of the legendary Eight Immortals in Taoism, further expanding her spiritual dimensions. These immortals are celebrated figures representing different aspects of transcendence, wisdom, and harmony with nature. Lü Dongbin, known for his wisdom and mastery of internal alchemy, is thought to embody the transformative potential of the human spirit. The connection between Datsueba and the Eight Immortals underscores her role as a liminal figure, bridging the earthly and spiritual realms.

Spiritual Space and Worship

Statues of Datsueba, whether enshrined individually or as part of larger groups, contribute to creating a sacred space that marks the boundary between the material and the spiritual. Halls dedicated to her, often called Ubason or Datsueba halls, serve as physical reminders of the transition between life and death. These spaces are designed to evoke introspection and reverence, encouraging worshippers to reflect on their own mortality and the karmic consequences of their actions.

The devotional practices surrounding Datsueba often emphasize her role as a guide through the metaphysical landscape. Her presence in rituals serves as a reminder that the journey through life and death is not solitary but is guided by forces that balance judgment with compassion.

A Modern Perspective

Datsueba remains a compelling figure in contemporary Japanese spirituality, her imagery and narratives continuing to inspire reflection on the human condition. As a symbol of impermanence, transformation, and the interconnectedness of life and death, she invites worshippers to confront their own attachments and embrace the path to spiritual awakening. Through her evolving roles and the diverse traditions that venerate her, Datsueba exemplifies the dynamic interplay between folk beliefs and established religious practices, offering a timeless lesson in the art of living and dying.

Datsueba’s essence, steeped in themes of transition, transformation, and spiritual examination, resonates profoundly with the Yoga of the Inner Light and the Illusory Body Yoga. These two yogic paths, rooted in meditative exploration of light and the recognition of the transient nature of self and existence, find an intriguing mirror in the symbolic role of Datsueba within Buddhist and folk traditions.

Datsueba and the Yoga of the Inner Light

In the Yoga of the Inner Light, practitioners focus on perceiving the radiant, luminous awareness that underlies all phenomena. This inner light is seen as both the essence of the self and a reflection of the divine, transcending the boundaries of the material world. Datsueba, in her role as the “Clothes-Snatching Old Hag,” can be interpreted as a guide to stripping away the veils of illusion—attachments, fears, and identifications with the physical form—that obscure the inner light.

Her act of removing the garments of the deceased symbolizes the removal of external distractions, enabling the soul to confront its true, luminous nature. Just as the Yoga of the Inner Light teaches that the radiant awareness is ever-present yet often hidden by the mind’s clutter, Datsueba’s role highlights the necessity of surrendering attachments to perceive the light of truth. In this way, she embodies a transformative process akin to turning one’s attention inward to discover the golden flower of pure consciousness described in Taoist and Buddhist texts.

Datsueba and the Illusory Body Yoga

The Illusory Body Yoga, on the other hand, challenges the practitioner to experience the body as a projection of consciousness, a phenomenon that arises within the luminous mind. This practice emphasizes detachment from the gross physical body and an awareness of the ephemeral, dream-like quality of all existence. Datsueba’s skeletal, gaunt appearance—a stark reminder of mortality—aligns with the teachings of Illusory Body Yoga, which stress the impermanence and non-substantiality of the physical form.

Datsueba’s dual role as a judge and guide mirrors the yogic process of self-examination. She compels the soul to confront its karmic imprints and attachments, much like how the Illusory Body Yoga directs practitioners to observe the body as a temporary construct within the vast space of consciousness. Her form, with exposed ribs and weathered features, embodies the illusory and transient nature of the body, urging practitioners to look beyond physicality and into the boundless essence of awareness.

The Bridge Between Traditions

Datsueba’s association with the Lotus Sutra further integrates her symbolism into these yogic paths. The Sutra’s emphasis on the universality of Buddha-nature aligns with the goal of perceiving the inner light as a universal truth accessible to all. Her submission to the Sutra’s power underscores the transformative potential of realizing one’s luminous essence—a core tenet of both the Yoga of the Inner Light and Illusory Body Yoga.

In modern practice, integrating Datsueba’s symbolic essence into these yogic paths offers a powerful framework for spiritual exploration. Her role as a guide through the borderlands of existence parallels the meditative journey inward, where the boundaries of self dissolve, and the radiant truth of interconnectedness is revealed.

Datsueba as a Symbol of Liberation

Ultimately, Datsueba, with her multifaceted roles and profound symbolism, serves as a reminder that spiritual liberation lies in embracing the impermanent, illusory nature of existence while turning inward to discover the eternal light of awareness. By linking her essence to the Yoga of the Inner Light and Illusory Body Yoga, practitioners can draw inspiration from her transformative power and gain deeper insight into the path toward spiritual awakening.

Bosch en Duin, 26-12-24/JMKH