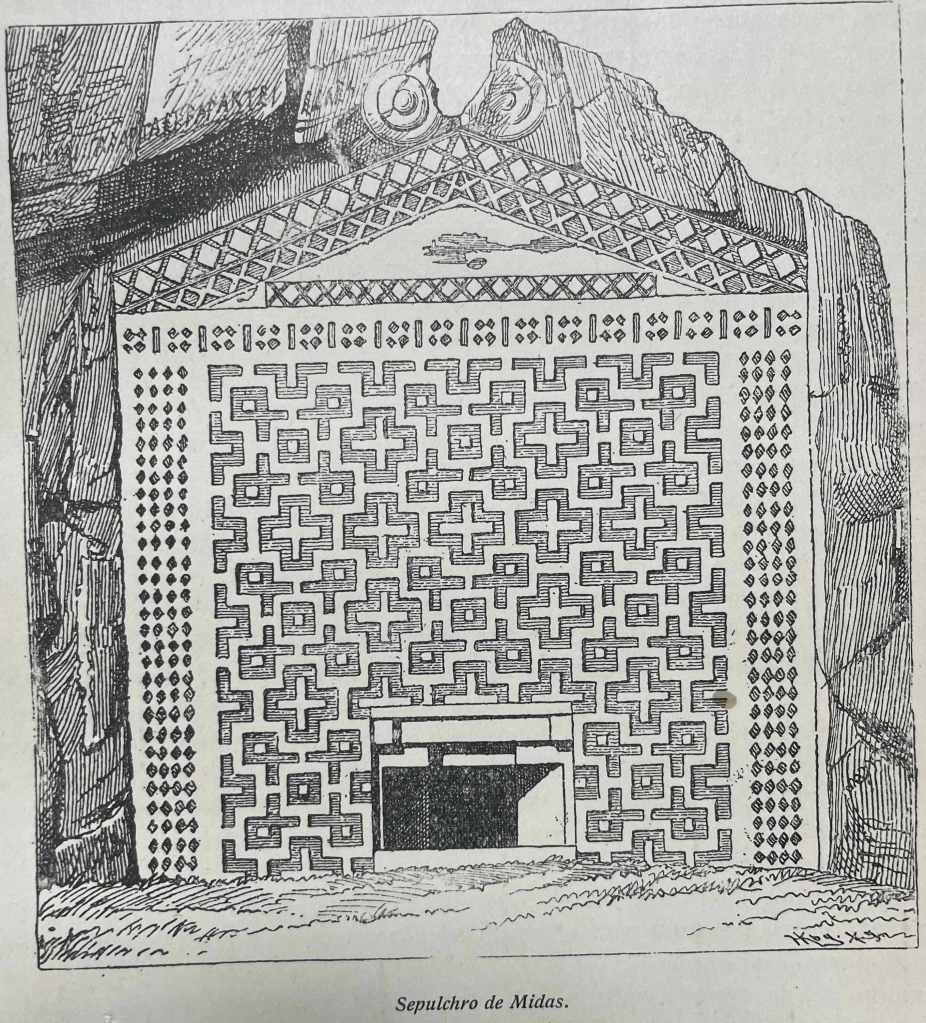

It was during a recent deep dive into an old, leather-bound, 20-volume series titled Historia Universal de Guilherme Oncken – a magnificent 19th-century universal history – that I stumbled upon a truly thrilling discovery. On page 15 of Volume 2, illustrating the “Sepulchre of Midas,” I found not a burial mound as I might have expected, but a striking image: the front of a temple carved directly into a natural rock formation. What immediately captivated me were its elaborate symmetrical cross-like structures and intricate geometric patterns covering the entire façade.

This monumental Midas Monument at Yazılıkaya, located in ancient Phrygia, immediately sparked a powerful connection to my phosphene research. The patterns are not accidental; they are highly stylized and repetitive. This observation leads to a compelling hypothesis: Could these ancient geometric carvings, so reminiscent of internally generated phosphenes, be visual records or depictions of what early humans experienced in altered states of consciousness?

Indeed, the very nature of these ancient Phrygian rock-cut sanctuaries suggests rituals that involved intense visual engagement. The sites often overlook vast landscapes, featuring altars and niches for deities, inviting focused attention. While direct evidence of “intense gazing” rituals from that era is scarce, the ecstatic nature of the Phrygian Mother Goddess Cybele’s cult, as described in later accounts, points to practices aimed at inducing altered states. Staring at such complex, repetitive patterns, whether on a rock face or in a sacred space, can naturally induce shifts in visual perception and, for some, trigger entoptic phenomena like phosphenes.

The Universal Visual Language: From Phosphenes to Art

This takes us to an even broader, more profound insight. It has long been observed that the earliest symbolic expressions of humanity, found in ancient rock carvings and petroglyphs, bear a striking resemblance to the spontaneous doodles and drawings of young children. These shared patterns – circles, zigzags, spirals, grids, crosses – seem to be universal.

This phenomenon finds a powerful explanation in the work of Ernst Haeckel, the 19th-century German biologist, who proposed the “biogenetic law”: “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” – the development of an individual organism (ontogeny) briefly reflects its evolutionary history (phylogeny). While Haeckel’s theory is largely discredited in its strict biological form, its metaphorical resonance is strong here. In a symbolic sense, the child’s development of basic visual forms might indeed “recapitulate” humanity’s earliest artistic expressions.

And the common thread? Phosphenes. These endogenous visual patterns, hardwired into the human visual system, serve as a primal, universal visual vocabulary. They are the “inner cinema” that arises spontaneously. It’s highly plausible that these internally generated geometric patterns, experienced in deep meditation, trance states, or even everyday visual noise, were a fundamental source of inspiration for both our ancient ancestors’ symbolic art and our children’s innate creative expressions. The Midas Monument, with its intricate phosphene-like patterns, becomes a stunning testament to how our inner luminous experience has manifested in the earliest and most profound forms of human art and spiritual iconography across millennia.

This integrated understanding deepens our appreciation for the universality of consciousness, the timelessness of contemplative practices, and the profound way our inner light has shaped human culture and our perception of reality throughout history.