We discuss first the results of this study: “Kvašňák, E., Orendáčová, M., & Vránová, J. (2022). Phosphene Attributes Depend on Frequency and Intensity of Retinal tACS. Physiological research, 71(4), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.934887″

The study is extremely valuable to define the form constants which can be percieved with closed eyes, as internal light phenomena. We will then generate a new taxonomy of Klüver formconstants.

What is a Form constant?

Form constants are recurring geometric or structured visual phenomena that emerge in the absence of external visual stimuli, typically during altered states of consciousness or under neurophysiological stimulation. These forms exhibit invariant structural patterns across individuals and modalities of induction, such as spirals, lattices, tunnels, and webs. They are typically experienced as luminous, two- or three-dimensional, and may be static or dynamically evolving.

This study explores how transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) applied near the eyes can elicit phosphenes: visual sensations such as flashes, dots, or geometric patterns that occur without actual light entering the eyes. The researchers aimed to understand how different stimulation frequencies and intensities influence the type, frequency, and dynamics of these inner light experiences.

Methods

A total of 62 healthy young adults participated, though only 50 were included in the final analysis due to data quality. Each participant received six types of brain stimulation in randomized order: anodal tDCS, cathodal tDCS, and four tACS frequencies (6 Hz, 10 Hz, 20 Hz, and 40 Hz). The study used a within-subject design, meaning each participant experienced all forms of stimulation. Sham stimulation was excluded to avoid participant fatigue and procedural complications.

Results

Nearly all participants reported phosphenes during all four tACS frequencies, with 92 to 98 percent effectiveness across conditions. In total, 41 distinct types of phosphenes were reported. Common types included flashes and circles, but rarer descriptions included spirals, checkerboards, tunnels, and moving lights—many of which align with known categories of form constants described by Klüver.

Importantly, the frequency of tACS was strongly correlated with the number of different phosphene types perceived. Lower frequencies (6 and 10 Hz) tended to produce fewer varieties, while higher frequencies (20 and 40 Hz) generated a greater diversity of forms. Additionally, increasing the intensity of tACS influenced several phosphene attributes, including brightness, size, motion, and occurrence rate. Up to nine different attributes were found to vary with intensity, although color changes were rarely reported.

The findings confirm that retinal tACS at a wide range of frequencies reliably triggers phosphenes in most individuals. The diversity and richness of perceived forms increase at higher frequencies, potentially due to interactions with endogenous brain rhythms in frontal regions. Higher tACS frequencies may amplify neural arousal and memory functions, thus enhancing perceptual detail and recall. The study also supports the idea that some phosphene types are universal, reoccurring across individuals and stimulation methods, possibly due to shared neural architecture

This research demonstrates that tACS is a powerful method to induce rich, varied phosphene experiences in healthy participants. The type and attributes of phosphenes depend on both the frequency and intensity of the stimulation. We will use the study to dive deep in the phenomenology of phosphenes.

The phenomenology of phosphenes in detail

The phenomenology of the reported phosphenes includes aspects of form, motion, brightness, color, spatial layout, and frequency of occurrence. The following typology is derived from both common and rare descriptors, grouped by thematic similarity.

Frequently Reported Phosphene Types

- Light flashes

The most commonly described experience. These were brief, sometimes repetitive bursts of inner light. Participants reported them as bright, sometimes flickering, and appearing spontaneously. They were seen under all four tACS frequencies, with 14 percent of participants reporting them consistently under all conditions. - Circles and round lights

Participants often described luminous circles, sometimes pulsing or flickering. These were generally uniform in brightness and size, and occasionally appeared with a soft glowing border. They were sometimes nested or concentric. - Vertical and horizontal lines

Straight luminous lines that extended across the visual field, with some reports suggesting motion or slight wavering. These were sometimes described as part of a more complex grid or structural pattern.

Geometric and Structured Forms

- Stripes and grids

Linear forms arranged in repetitive patterns, including stripes aligned in one or multiple orientations and rectangular grid structures. These often conveyed a sense of artificiality, as if seen through a screen. - Checkerboards and pixels

Some participants described black-and-white or monochrome checkerboard patterns, and pixelated fields resembling a digital screen with low resolution. - Spirals

Swirling luminous forms, sometimes in motion, creating a vortex-like or funnel appearance. These forms were rare but distinct, and appeared primarily at higher stimulation frequencies. - Tunnels and concentric circles

Cylindrical or funnel-like visuals, giving the sensation of depth or motion into a central vanishing point. Participants sometimes referred to these as a tunnel or corridor of light. - Cobwebs or lattices

Fine thread-like structures or meshworks, evoking the sensation of being inside a delicate luminous web. These were often associated with the form constants described by Klüver.

Less Common or Singular Descriptions

- TV grains and snowing

Descriptions such as visual static, sparkling dots, or noisy textures, reminiscent of analog television static. These fields often lacked structure but conveyed a continuous flickering activity. - Dots and sparkles

Punctate, bright visual points scattered across the field, sometimes blinking or twinkling. Some participants described these as stars or glimmers. - Blobs and bubbles

Round, soft-edged luminous forms, sometimes translucent or colored. They evoked associations with soap bubbles or oil on water. - Water-related visuals

Several descriptions evoked liquid dynamics, such as waves, a waterfall, or the shimmering of light on the surface of water. These forms were often reported as dynamic and gently flowing. - Oblique or perpendicular lines

Crosshatched line structures and diagonal patterns were reported, sometimes with a sense of spatial layering or three-dimensionality. - Light fans and scattered beams

Some participants reported forms resembling a fan of light or scattered luminous lines, extending radially from a central origin. - Comb shapes and brackets

Forms that had the appearance of comb teeth or bracket-like structures, often flickering or appearing rhythmically. - Twinkles and blinking bulbs

Tiny, irregular points of light that turned on and off unpredictably, often resembling fairy lights or Christmas tree lights. - Curves, rhombuses, and rectangles

These included angular and curved forms, some of which were symmetrical. The rhombus shapes were reported as rare, while rectangles and curves appeared more often under 20 Hz and 40 Hz stimulation. - Concentric forms and carousels

Rotating or nested structures, creating a sense of spiraling or layered motion. - Auras and halos

Descriptions included light surrounding imagined objects or figures, often circular and softly diffused. - Mixtures of colors and vague coloration

Though most phosphenes were reported as colorless or white, some participants mentioned subtle mixtures of pale colors, though this attribute was among the least frequently noted. Color changes were rare across all frequencies and occurred in less than three percent of cases.

Dynamic Attributes of Perception

The study identified nine attributes that changed depending on the intensity of stimulation:

- Type of phosphene (form)

- Size of the phosphene

- Brightness

- Frequency of occurrence during stimulation

- Simultaneous presence of multiple phosphene types

- Type of movement

- Speed of movement

- Trajectory of movement

- Color (very rarely reported)

Forms were often seen to pulse, move in circular or oscillating trajectories, or drift across the visual field. Some phosphenes appeared centrally; others seemed to arise in the peripheral visual field. While some were brief flashes, others lasted the duration of the stimulation and were layered with motion and structure.

Recurrence and Subjective Preferences

Certain forms appeared repeatedly in the same individual across multiple stimulation frequencies. Light flashes were the most stable and recurring phosphene, followed by circular shapes and vertical lines. Some participants consistently reported the same form under two, three, or all four tACS frequencies, suggesting individual variability in phosphene susceptibility and perceptual structuring.

The variety and richness of phosphene forms described in this study point toward a structured yet fluid internal visual landscape, responsive to frequency and intensity of neural stimulation. Many reported forms echo classical categories of entoptic phenomena, such as Klüver’s form constants, while others appear more spontaneous or idiosyncratic. The descriptions illustrate a continuum from simple flashes and dots to complex patterns of depth, motion, and geometric intricacy. These findings strengthen the notion that phosphenes are not merely random inner events, but may reflect deep structural tendencies of the visual and neural system when decoupled from external visual input.

Mapping the Induced Phosphenes onto the Phosphene Taxonomy

Our taxonomy of phosphene experiences follows a gradual intensification and refinement of inner visual phenomena, generally progressing from diffuse and unstable percepts to coherent, dynamic, and symbolically resonant visionary imagery. The tACS-induced phosphenes, while artificially stimulated, mirror many spontaneous and meditative forms and provide empirical support for the universality and hierarchical nature of phosphene emergence.

Let us now integrate the forms from the study into our phosphene taxonomy:

Phase 1 – Flickers, Dots, and Afterimages

Correspondences:

- Light flashes

- Stars or twinkles

- TV snow, static, and pixelation

- Isolated dots or tiny sparkles

- Afterimages from imagined stimuli or candle meditation

Interpretation:

This phase corresponds closely to the earliest forms described under low-intensity or lower-frequency stimulation. These are formless or minimally-structured phenomena arising from minimal cortical or retinal excitation. The “TV static” and twinkling lights likely represent entoptic noise, residual excitation, or photoreceptor field-level activations. This supports our position that Phase 1 is governed by retinal-originated phenomena and afterimages, modulated by attention, stillness, and stimulus decay.

Phase 2 – Simple Geometries and Movement Initiation

Correspondences:

- Vertical and horizontal lines

- Moving dots or linear sparkles

- Slightly pulsing circles or rounded forms

- Faint cobwebs or lattices

- Flashing lights with trajectory or motion

- Waves and water shimmer patterns

Interpretation:

Here, visual forms become more spatially organized and introduce directionality or motion. These are the beginning of self-organizing patterns within the neural visual system, corresponding with what we have described as Phase 2: early geometric structuring and patterned flow. The frequent appearance of movement (especially of dots or flashes) indicates an activation of motion-processing pathways, suggesting involvement of early visual cortical areas (V1 to V3).

Phase 3 – Structured Patterns and Form Constants

Correspondences:

- Checkerboards

- Grids

- Spiral forms

- Tunnels or vortex-like imagery

- Brackets, comb shapes

- Concentric circles

- Crosshatching and symmetry

Interpretation:

This phase aligns remarkably well with Klüver’s four form constants, spirals, tunnels, lattices, and cobwebs, all of which are richly represented in the tACS-induced phenomenology. These forms indicate a transition from diffuse or partial structure to full-field geometric complexity, often with recursive or self-similar characteristics. This supports our definition of Phase 3 as a structurally organized, internally stable visionary field, likely linked to sustained activation of the visual association cortex and feedback loops from attention networks.

Phase 4 – Kinetic and Dynamic Integration

Correspondences:

- Fans of light or radiating beams

- Light movement with clear trajectory

- Spirals in motion

- Layers of moving patterns

- Carousels, rotating forms

- Multiple simultaneous phosphenes

Interpretation:

Phase 4 is marked by dynamic interactivity within the inner visual field. The appearance of spirals, rotations, and multi-layered motion forms indicates the involvement of temporal integration and visual motion pathways. The perception of “multiple simultaneous phosphenes” further aligns with our model’s recognition that at this stage, the inner field becomes populated with co-existing, interacting elements, often with a distinct felt sense of depth or expansion. These dynamics are closely tied to the emergence of an inner space or visionary ‘arena.’

Phase 5 – Emerging Symbolic Structures and Light Bodies

Correspondences (inferred):

- Auras and halos

- Rare colored forms

- Full-field luminous movement

- Concentric whirling forms with internal structure

Interpretation:

While the tACS study does not provide many descriptions that clearly correspond to symbolic or archetypal imagery, the appearance of halos, color-infused forms, and multidimensional motion suggests the beginning of Phase 5 phenomena. In meditative practice, this stage is typically marked by the appearance of subtle symbols, archetypal geometries, and mythic imagery (such as mandalas or eyes). The induced phosphenes in this study show the potential of external stimulation to approach this level, though without the symbolic integration normally evoked in prolonged contemplative states.

Phase 6 – Blinding Light and Supra-formal Radiance

Correspondences (absent in tACS data):

- This level, described as pure, overwhelming inner radiance or consciousness-saturating light, was not reported in the study. This is consistent with the understanding that Phase 6 reflects a culmination of self-generated visionary states, not easily evoked by artificial stimulation. It involves not just perceptual structure but full affective and transpersonal integration, often described as ego-dissolving, mystical, or divine.

Additional Insights from the Study

- The correlation between frequency and number of forms suggests that higher tACS frequencies (beta and gamma) generate richer perceptual phenomena. This supports our idea that vibratory intensity, whether endogenous or induced, facilitates access to higher-level phosphene stages.

- The modulation of up to 9 distinct phosphene attributes with changing intensity mirrors what advanced practitioners report during deepening meditative absorption. Size, brightness, speed, color, and complexity are all experiential markers that we also use to distinguish developmental stages.

- The repetition of certain forms across participants aligns with the notion of universal neural structures governing phosphene production, consistent with both Klüver’s model and our own phosphene architecture.

Conclusion: meditation is not the same as transcranial brain stimulation….

The tACS-induced phosphenes, though artificial, provide empirical evidence for a hierarchical unfolding of inner light phenomena that closely tracks our phenomenological taxonomy. This suggests that the inner light pathway of meditative development reflects not only subjective evolution but a lawful structure of visual and neurophysiological potentialities. The artificial induction of structured phosphenes validates the depth and universality of the meditative journey we have described and provides a foundation for further scientific and contemplative exploration.

There are important differences between phosphenes that arise during deep meditation and those that are elicited through mechanical or electrical stimulation, such as transcranial alternating current stimulation or physical pressure on the eyeballs. Although both forms of phosphene induction engage the visual system and reveal the capacity of the nervous system to generate internal light phenomena, their origin, phenomenology, and depth of experience differ in profound ways.

Meditation-induced phosphenes are generated from within. They emerge spontaneously as the mind becomes still and perceptual sensitivity increases. These inner lights often appear gradually, arising in moments of silence, darkness, or intentional focusing. They evolve with time, sometimes becoming complex, meaningful, and richly patterned. They reflect an inner coherence and seem to be guided by a subtle intelligence or logic. Many practitioners report that the lights are not merely visual disturbances, but doors into deeper levels of awareness, accompanied by feelings of awe, joy, or spiritual presence.

In contrast, mechanically provoked phosphenes are triggered externally. They are usually produced through stimulation of the retina or visual cortex, and their appearance depends on technical parameters such as frequency, intensity, and electrode placement. These phosphenes often appear immediately upon stimulation and disappear when the stimulus is removed. While they can include simple forms such as flashes, dots, stripes, spirals, or grids, they are usually fleeting, fragmentary, and emotionally neutral. There is no sense of symbolic unfolding or progression toward deeper states of consciousness.

The emotional resonance of the two experiences is also quite different. Meditative phosphenes often carry a strong affective tone. They can be accompanied by bliss, reverence, or the feeling of being drawn into a visionary world. These lights sometimes transform into mandalas, radiant eyes, sacred geometries, or subtle presences that communicate meaning beyond words. In comparison, mechanically induced phosphenes are more like laboratory artifacts. They are fascinating as sensory phenomena but are not usually remembered as significant or transformative. They lack the depth of personal and spiritual meaning that characterizes the inner lights seen in contemplative practice.

Another key distinction lies in the stability and responsiveness of the experience. Through practice, meditators often develop a refined capacity to dwell in the phosphene field, to observe its transformations, and even to stabilize or navigate the inner imagery. The lights become more vivid, more structured, and more reliable over time. In contrast, phosphenes induced by artificial means are less stable and cannot be directed or influenced by the subject. They come and go according to changes in the stimulation, not the state of the practitioner.

Symbolic and archetypal development is one of the most remarkable features of meditation-induced phosphenes. Over time, the practitioner may witness increasingly complex imagery arising from the light: shapes that resemble mandalas, deities, inner suns, or visionary landscapes. These experiences often feel imbued with a sense of guidance or sacred revelation. Mechanically induced phosphenes may occasionally include classic geometric forms, such as spirals or tunnels, which have been described as part of Klüver’s form constants. However, they rarely develop into structured or symbolic imagery and do not unfold into visionary sequences.

The inner state of the practitioner also plays a decisive role. Meditation typically induces a calm, open, and receptive state of consciousness, associated with physiological coherence and deep inward focus. This state supports the perception of subtle lights and enhances their integration into awareness. In contrast, mechanical stimulation does not cultivate any particular mental state. It may even disrupt the meditative field by introducing discomfort, distraction, or a sense of artificiality.

In summary, while both types of phosphene can be mapped and categorized, they belong to very different domains of experience. Mechanical methods help us understand the nervous system’s visual capacities, but meditation reveals the luminous architecture of consciousness itself. The inner light accessed through contemplative practice is not merely a neurological echo but a gateway into meaning, depth, and transformation.

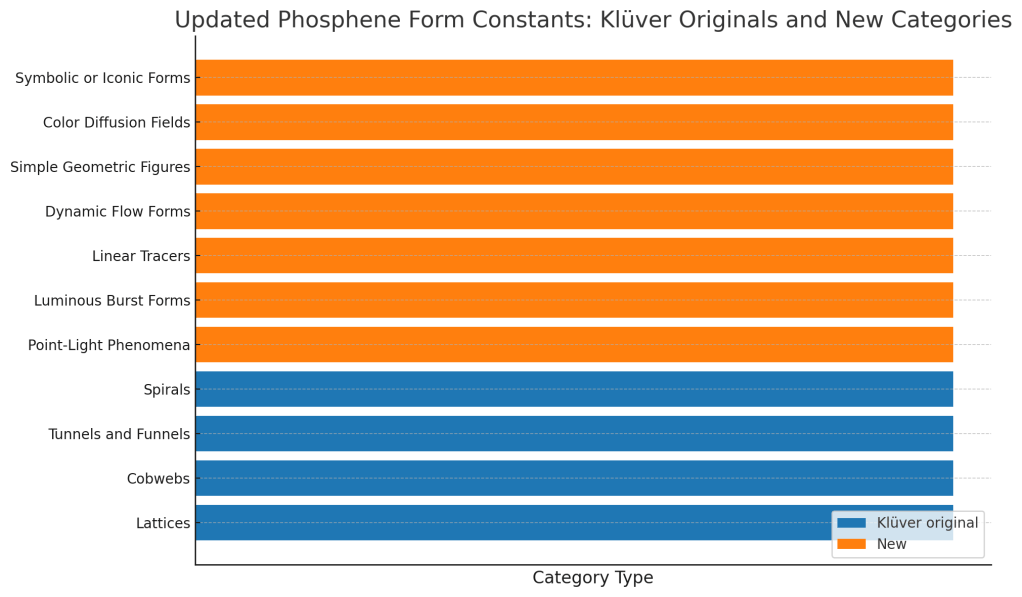

The study we discussed here seem thus to expands significantly on the classic four form constants identified by Heinrich Klüver (1942), which are:

- Lattices (grids, checkerboards, honeycombs)

- Cobwebs

- Tunnels (spirals, funnels)

- Spirals

These were considered universal structures observed in hallucinations and visual phenomena, especially in mescaline experiences.

In contrast, the tACS study documented 41 distinct phosphene types, of which only a few overlap with Klüver’s categories.

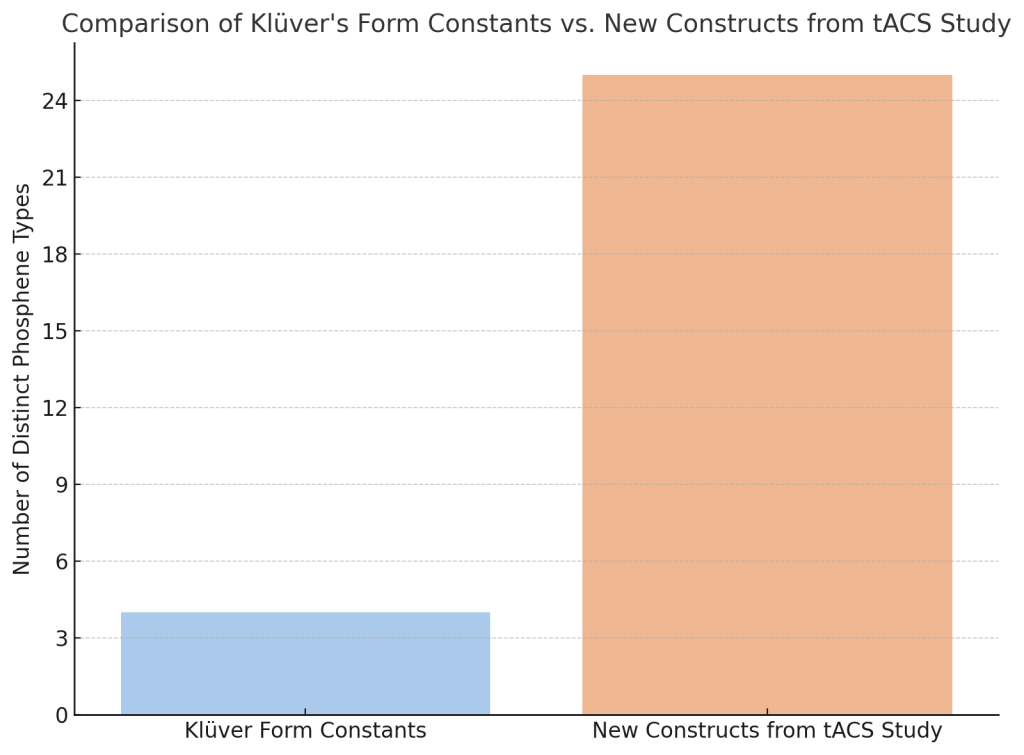

This bar chart illustrates the expansion in the taxonomy of phosphene types. Klüver originally identified four core categories of form constants: lattices, cobwebs, tunnels, and spirals. In contrast, the recent tACS study documented 25 distinct phenomenological constructs not clearly reducible to Klüver’s schema. This suggests a significant enrichment of descriptive diversity when phosphenes are mechanically induced under controlled stimulation protocols.

These newly described constructs include highly specific forms such as grids, oblique lines with depth impression, checkerboards, waterfalls, and concentric fans, pointing toward a much broader and more nuanced visual vocabulary of phosphene perception. This expanded repertoire could help refine our phenomenological taxonomy and distinguish between mechanical and endogenous sources of visual experience.

Let’s compare them in detail:

Constructs overlapping with Klüver:

- Spirals → directly mentioned

- Tunnels → directly mentioned

- Checkerboard → part of lattices

- Grid, stripes, vertical lines, horizontal lines, rhombus, concentric shapes → can all fall under “lattices/gratings”

- Cobwebs not explicitly mentioned, but possibly included under “filigree” forms

New perceptions beyond Klüver:

These are the phenomenological constructs that seem new or at least not classifiable under Klüver’s original taxonomy:

- Light flashes

- Light circles, round lights, circles, spot

- Dots, pixels

- TV grains

- Twinkles, sparkles

- Snowing

- Waves, waterfall, water surface

- Light in water surface

- Carousel

- Light fan

- Blinding bulb, gazing at the lamp

- Oblique lines with impression of depth

- Lines with unspecific orientation

- Scattered lines

- Semicircle

- Bracket

- Bubble

- Rectangle

- Stellar shapes

- Mixture of colors

- Aura around things

- Comb

- Lines perpendicular to each other

Are these really form-constructs? No!

The 23 forms from the tACS study should be seen as raw phenomenological data, useful for expanding our descriptive atlas of phosphene perception. However, they are not yet formal constructs like Klüver’s.

These newly reported types reveal:

- Greater richness of dynamic visual texture

- A mix of simple geometric forms (dots, lines, rectangles)

- Atmospheric or metaphorical descriptions (e.g., “snowing,” “aura,” “TV grains”)

- Possible influence of modern visual culture (e.g., “pixels,” “TV grains”)

This suggests that tACS-induced phosphenes can reveal a broader spectrum of form constants, possibly a new phenomenological taxonomy that supplements Klüver’s. Let us see what in essence did this study add to the form constants of Klüver. So that we can enrich Klüver’s legacy in this field.

Updated Taxonomy of Klüver’s form constants of phosphenes

The present analysis of phosphenes induced by transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) provides an unprecedented opportunity to revisit and expand the foundational typology of form constants established by Heinrich Klüver in the mid-twentieth century. Klüver’s system, based primarily on the effects of mescaline and other psychedelics, proposed four recurrent geometric forms observed across subjects and contexts: lattices, cobwebs, tunnels, and spirals. These categories have since been validated in numerous pharmacological and neurological studies and are often seen as the core phenomenological constants of inner vision.

Yet, the phenomenology of phosphenes elicited by electrical stimulation opens up a wider and perhaps more dynamic palette of inner visual forms. In the study under consideration, participants reported more than forty distinct types of phosphenes induced across different frequencies of tACS, ranging from simple flashes and dots to complex grid patterns, curving movements, and symbolic or representational shapes. When these forms are compared to Klüver’s constants, some map cleanly onto the original typology, while others elude classification, suggesting the need for an updated and expanded system.

To proceed methodically, we have grouped all reported phosphene types into three categories:

- Forms that clearly fit within one of Klüver’s original constants

- Forms that only partially overlap with Klüver’s categories or constitute dynamic or transitional variants

- Forms that do not fit any classical category and suggest new constants

Below is an integrated table that lays out the raw phosphene types and their tentative classification:

| Phosphene Description | Classification |

|---|---|

| Checkerboard, grid, stripes | Lattice (Klüver) |

| Lines perpendicular to each other | Lattice (Klüver) |

| Pixels, comb, TV grains | Lattice (Klüver) |

| Concentric, circular aura | Cobweb (Klüver) |

| Tunnel, carousel, light fan, waterfall | Tunnel/Funnel (Klüver) |

| Spiral | Spiral (Klüver) |

| Oblique lines with impression of depth | Spiral or Tunnel (Klüver) |

| Twinkles, sparkles, blinking bulb, snowing | Point-Light Phenomena (New) |

| Dots, spot, stars | Point-Light Phenomena (New) |

| Light flashes, round lights, gazing at the lamp | Luminous Burst Forms (New) |

| Vertical and horizontal lines (isolated) | Linear Tracers (New) |

| Waves, scattered lines, curves | Dynamic Flow Forms (New) |

| Rectangle, rhombus, semicircle, bracket | Simple Geometric Figures (New) |

| Mixture of colors | Color Diffusion Fields (New) |

| Stellar shapes | Symbolic or Iconic Forms (New) |

| Bubble, light in water surface | Cobweb or Dynamic Flow (Ambiguous) |

This table reveals that while Klüver’s categories remain highly relevant, they capture less than half of the forms observed in the tACS-induced phosphene data. This prompts the proposal of several new phenomenological categories that could extend the original typology.

The first is what we may call Point-Light Phenomena. These refer to minimalistic light points—twinkles, sparkles, or snow-like dots—without fixed geometric organization, yet recurrent across participants. Their subtlety and dynamism make them a foundational perceptual unit, perhaps analogous to pixels in digital vision.

A second proposed category is Luminous Burst Forms. These include flashes of light or bulb-like radiance that seem more explosive or pulsatile than structured. Unlike Klüver’s lattices or cobwebs, these forms are temporally accentuated and lack repetitive geometry.

A third emergent class could be termed Linear Tracers. These are simple lines, either horizontal or vertical, perceived without integration into a full grid or tunnel structure. While such lines might be embryonic lattices, their isolated presentation calls for an independent recognition.

We also propose a group called Dynamic Flow Forms, encompassing curvilinear, wave-like movements that are neither strictly geometric nor random. These forms are often reported with a sense of movement or flow, sometimes compared to water or wind.

In addition, several reports describe Simple Geometric Figures—rectangles, semicircles, rhombuses—that fall outside of Klüver’s four groupings. While individually basic, these forms imply a kind of symbolic or constructed visual architecture that deserves its own phenomenological bracket.

The Color Diffusion Fields category accounts for rare mentions of color blending or chromatic gradients, which are not well captured in Klüver’s black-and-white scheme. Although infrequent in the current dataset, such descriptions may become more prominent in other experimental conditions.

Lastly, we note a small but meaningful group of Symbolic or Iconic Forms, such as “stellar shapes” or possibly even the impression of “aura around things.” These may hint at archetypal or culturally embedded visual forms that surpass simple geometry.

This expanded taxonomy does not aim to replace Klüver’s system but to extend it in light of contemporary stimulation research. It opens a path toward a more nuanced phenomenology of phosphenes that includes temporal, chromatic, and symbolic dimensions. Moreover, this refined classification may serve as a bridge between different induction techniques—chemical, mechanical, electrical, and meditative—and allow for a unified comparative framework.

Further studies should quantify the relative frequencies of these new categories across stimulation modalities, levels of arousal, and training background of participants. Just as Klüver’s constants became a cornerstone of early neurophenomenology, this updated schema may contribute to a more granular understanding of the visual mind and its latent geometries.

Updated Classification Table of Phosphene Form Constants

| Category | Type | Examples from Reports | Descriptive Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lattices | Klüver original | Checkerboards, grids, interlacing lines, pixel grids | Repeating 2D patterns, often symmetric, angular or rectangular |

| Cobwebs | Klüver original | Concentric circles, aura rings | Radiating or layered circular patterns, centered or expanding |

| Tunnels and Funnels | Klüver original | Tunnel, carousel, funnel, vessels | 3D perspective shapes, often with inward motion or depth |

| Spirals | Klüver original | Spirals, rotating arms | Coiled shapes, curved motion, often suggest inward or outward flow |

| Point-Light Phenomena | New | Twinkles, sparkles, blinking dots, stars, snowing | Tiny light points, often moving, flashing or scattered in space |

| Luminous Burst Forms | New | Light flashes, round lights, gazing at a lamp | Sudden or pulsating lights, brief and intense, without form |

| Linear Tracers | New | Isolated vertical and horizontal lines | Simple linear elements not forming grids, static or moving |

| Dynamic Flow Forms | New | Curves, waves, scattered lines, light in water surface | Flowing, undulating patterns, often with implied motion or texture |

| Simple Geometric Figures | New | Rectangle, rhombus, semicircle, bracket shapes | Discrete geometric elements, may appear symbol-like or architectural |

| Color Diffusion Fields | New | Mixed colors, color gradients | Chromatic spread or diffusion, rare in this dataset |

| Symbolic or Iconic Forms | New | Star shapes, aura outlines, bracket motifs | Forms suggestive of cultural or symbolic imagery |

Now there are more sources we have to examine in order to create a fully updated table.

Below is the comprehensive table with three sections: Klüver constants, tACS‑based new categories, and additional categories from broader sources:

| Category Name | Origin | Examples / Examples from Reports |

|---|---|---|

| 1.Lattices / Grids | Klüver original | Checkerboards, grids, stripes, pixelated forms |

| 2.Cobwebs | Klüver original | Concentric rings, auras, radial patterns |

| 3.Tunnels / Funnels | Klüver original | Tunnel, funnel, carousel, spiral depth forms |

| 4.Spirals | Klüver original | Coiling forms, vortexes |

| 5.Point-Light Phenomena | tACS study | Twinkles, sparkles, stars, isolated dots |

| 6.Luminous Burst Forms | tACS study | Flashes, round bulbs, sudden bright events |

| 7.Linear Tracers | tACS study | Isolated horizontal or vertical lines |

| 8.Dynamic Flow Forms | tACS study | Curves, waves, scattered lines, waterfall-like visuals |

| 9.Simple Geometric Figures | tACS study | Rectangles, rhombuses, semicircles |

| 10.Color Diffusion Fields | tACS study | Subtle color blends, mixtures |

| 11.Symbolic / Iconic Forms | tACS + meditation | Star shapes, mandalic hints, aura-symbol forms * |

| 12.Floating Field Forms | pressure / adaptation / migraine | Amorphous glow, dream-like misty patches |

| 13.Pulsating / Breath-Linked Forms | meditation reports | Light forms expanding-contracting with breath or attention |

| 14.Vibratory or Oscillatory Forms | EEG-linked studies | Forms shimmering or flickering at alpha, beta, or gamma rates** |

| 15.Radiant Full-field Light | advanced meditation / CEV levels*** | Uniform light filling entire field of perception |

| 16.Textural Noise or Visual Snow Forms | migraine / visual snow syndrome | Static-like patterns, fine grain noise visual texture |

With these additions, we have a holistic classification that:

- Honors Klüver’s original four form constants,

- Incorporates the rich descriptive categories emerging from tACS-induced phosphene reports,

- Adds phenomenological categories supported by other contexts such as pressure-induced, migraine-related, or meditative inner light experiences.

These 15 categories offer a robust updated taxonomy, bridging geometry, motion, sensory texture, symbolic depth, and meditative dynamics.

Explanation of * ** etc

*The term aura-symbol forms (as mentioned in the updated table under “Symbolic / Iconic Forms”) refers to inner visual impressions that resemble simplified spiritual or archetypal symbols, often appearing spontaneously during altered states like meditation, phosphene stimulation, or migraine aura. These forms are not purely geometric (like Klüver’s lattices or spirals) but carry a symbolic or iconic resonance. Here’s a clarification:

Aura-symbol forms are inner light visuals that resemble or evoke meaningful symbolic images, such as stars, halos, eyes, crosses, radiant mandalas, or divine geometries, without necessarily being full religious visions. They often appear spontaneously as part of the subjective visual field in states of heightened attention, inner silence, or neuro-electrical stimulation, such as:

- A bright five- or six-pointed star with a pulsing center

- A circular light form that evokes a halo or sun disk

- A cross-shaped glow or symmetrical division of light

- A mandala-like pattern without detail, just radiating structure

- The “eye” shape reported in both psychedelia and deep meditation

They differ from complex formed visions (like full deities or faces) because they’re minimal and suggestive, not imagistic or narrative. They differ from Klüver form constants because they carry semantic or archetypal significance, rather than being just neurological pattern recognition.

In EEG-linked phosphene studies, participants sometimes describe forms that are “meaningful” or “sacred” despite being simple shapes. In migraine aura, people sometimes report “crosses,” “stars,” or “holy forms” before the headache onset.nIn meditation, subtle archetypal lights may emerge before full visionary experiences—these can be symbolic thresholds.

** alpha, beta, or gamma rates: When participants report that a phosphene or visual form is shimmering or flickering at alpha, beta, or gamma rates, they are describing a dynamic quality of their visual experience. These forms do not remain static but instead fluctuate in brightness, clarity, or outline at regular rhythmic intervals. These rhythms correspond to known brainwave frequencies: alpha (approximately 8 to 13 hertz) produces a soft pulsing or gentle flickering, beta (13 to 30 hertz) gives rise to quicker fluttering sensations, and gamma (30 to 100 hertz) results in very rapid stroboscopic-like flashing. While participants do not measure these frequencies explicitly, the flickering can be linked to the stimulation frequency used during transcranial alternating current stimulation, or to internal oscillatory states during meditation.

Phenomenologically, these experiences are often described as lights or patterns that pulse, tremble, or vibrate. A participant might describe a grid or spiral that seems to shimmer rapidly, a tunnel form that appears to beat or breathe, or a diffuse light that flickers softly in and out of visibility. The flicker is not just a visual effect but can carry an emotional or somatic quality, contributing to the overall subjective impact of the phosphene experience.

In the context of tACS, these flickers often reflect the frequency of the applied current, such as 10 hertz stimulation producing an alpha-range flicker in perceived light patterns. In meditation-induced phosphenes, similar rhythms may arise spontaneously, linked to internal states of attention and arousal. For instance, meditative calm may correlate with alpha-like flickering, while moments of insight or intense focus might produce faster beta or gamma-range modulations.

This kind of flickering adds a temporal layer to the geometry of phosphenes. It transforms static forms like spirals, lattices, or tunnels into moving, breathing, or vibrating experiences. These rhythmic fluctuations may reflect oscillatory mechanisms in the brain and suggest that perception is not merely about form but also about timing and frequency. Thus, shimmering or flickering forms represent a bridge between the spatial structure of phosphenes and the underlying temporal dynamics of neural and conscious activity.

***CEV levels: The term “CEV levels” stands for Closed-Eye Visualization levels, a classification system used to describe the range and progression of visual experiences seen with the eyes closed. This model, which emerged from the work of researchers like John Lilly and others studying altered states of consciousness, attempts to map how visual imagery evolves across deepening states of inner perception, whether induced by meditation, psychedelics, trance, or sensory deprivation.

At the most basic level, individuals report simple patterns of light and color—swirling textures, moving dots, or flashes that lack clear form. These are often spontaneous and can arise during light meditation or simply when closing the eyes in darkness. As inner attention deepens, these basic visual elements begin to cohere into recognizable geometric patterns, such as spirals, tunnels, grids, or lattice-like structures. This stage often overlaps with known entoptic phenomena and the so-called form constants described by Heinrich Klüver.

Further along this continuum, the visual content becomes more complex and structured. People may begin to see symbolic shapes, faces, landscapes, or dreamlike sequences that seem to have meaning, even if unstable or fleeting. At this point, the mind no longer just perceives abstract form but begins to interpret and engage with it, leading into a deeper, emotionally resonant level of experience.

In more immersive states, typically achieved in intense meditation or under the influence of psychedelics, the viewer may find themselves inside visionary environments or interacting with autonomous-seeming entities. These experiences often carry strong emotional or spiritual charge and may be perceived as deeply personal or even transformative. At the highest levels, the visual field may dissolve entirely into vast luminous spaces, archetypal scenes, or a sense of complete unity, where ego boundaries vanish and time seems suspended. These final stages are frequently described in reports of mystical union or near-death experiences.

In the context of phosphene research and the Yoga of Inner Light, most experiences described fall within the earlier CEV levels—especially those involving geometric forms, flashes, or simple shapes that arise during meditative concentration. However, with consistent practice, some individuals may cross into more advanced levels of closed-eye imagery, where phosphenes become the doorway to fully immersive inner journeys. The CEV framework offers a useful lens to understand this spectrum, highlighting the continuity between simple sensory effects and profound visionary states.

Here is a summary of the typical CEV levels:

- Level 1 – Abstract light and color

Simple, often swirling patterns, colors, or flickering lights. These are akin to basic phosphenes or form constants such as spirals or grids. Very common during relaxation, darkness, or light meditation. - Level 2 – Recognizable patterns and shapes

More structured imagery begins to emerge. These may include faces, landscapes, tunnels, or more vivid geometric forms. Still unstable or fleeting. - Level 3 – Vivid, dreamlike scenes

Scenes or objects appear lifelike and can shift like in dreams. Imagery may become complex, animated, or symbolic. - Level 4 – Interactive and emotionally charged imagery

The viewer may feel immersed in the scene. Emotions are intensified, and content may be personal or archetypal (e.g. meeting entities, traveling through symbolic worlds). - Level 5 – Autonomous visionary realms

Full immersion into seemingly autonomous realities with internally consistent logic. One may experience alternative worlds or spiritual revelations. This level is rarely achieved except with high doses of psychedelics or deep mystical states. - Level 6 – Complete disconnection from physical reality

Ego dissolution, loss of sense of body and time, entering voids or infinite light. Often described in near-death experiences, intense mystical episodes, or peak psychedelic states.

Shunyam Adhibhu