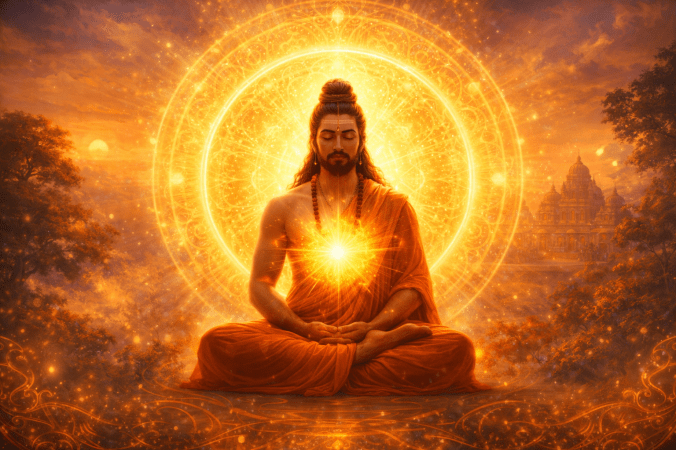

Kabir and the Yoga of the Inner Light

A Reading of the Chauntīsī part of Kabir’s Bijak

What Chauntīsī means? The word comes from Hindi: chauntīs = thirty-four. Chauntīsī = a composition consisting of thirty-four verses In Kabir’s corpus, texts are often grouped by metrical or numerical form, not by doctrinal topic. Examples include:

- Sakhi (couplets)

- Pada (songs)

- Ramaini

- Chauntīsī (34 verses)

The Chauntīsī is typically used for dense, technical instruction, not devotional storytelling. That already tells us something very important. If Kabir wanted to transmit interior practice rather than public devotion, he often did it in Chauntīsī form.

The Bijak of Kabir

In the 1917 English translation of The Bijak of Kabir by the Rev. Ahmad Shah, we encounter a short but remarkably dense instructional passage in that section titled Chauntīsī. At first glance, the language appears poetic and symbolic. On closer inspection, however, it reveals itself as something far more precise: a compressed phenomenological guide to inner luminous perception.

The passage reads:

“One may find the flame within the lotus.

When the mystic moon appears, its light cannot be quenched.

There if one gains the golden colour, he comprehends the incomprehensible,

and makes his mind’s abode in heaven.”

This fragment is not devotional ornamentation. It is not metaphor layered upon metaphor. It is instruction written in the concise and demanding style Kabir often uses when addressing interior practice rather than public religion.

The Form Matters: Why the Chauntīsī Is Important

In Kabir’s corpus, Chauntīsī compositions tend to be among the most technically dense. They are not narrative, not lyrical exhortation, but compact sequences intended to be worked with slowly, repeatedly, and inwardly.

In other words, Kabir chose this form when he wanted to transmit something that could not be explained discursively. That already suggests we are dealing with practice rather than belief.

The Flame Within the Lotus

The opening line, “One may find the flame within the lotus,” points to a stabilized inner phenomenon. The lotus here should not be read primarily as a later tantric chakra-symbol. In Kabir’s usage, it denotes an interior locus of attention, a place where awareness has become sufficiently still to perceive.

The flame is not metaphorical inspiration. It is a localized inner light, often reported in meditation as a steady point or small field of luminosity. Unlike fleeting flashes or visual noise, this flame is recognizable, repeatable, and relatively stable. It marks the transition from vague inner brightness to coherent perception.

The Mystic Moon That Cannot Be Quenched

Kabir then speaks of a “mystic moon” whose light “cannot be quenched.” This signals a qualitative shift. The imagery moves from flame to moon, from a localized point to a pervasive, cooling illumination.

The key phrase here is cannot be quenched. Kabir is describing irreversibility. The light no longer depends on effort, posture, or momentary concentration. It persists. Thought does not extinguish it. Emotion does not overwhelm it. The light has become self-sustaining.

This is a crucial marker in contemplative phenomenology. It indicates that awareness has crossed a threshold where inner luminosity is no longer a transient event but a stable condition.

The Golden Colour

Next comes the reference to “the golden colour.” This line has often been moralized or symbolized in later traditions, but Kabir’s usage is experiential. Gold here does not signify virtue or holiness. It refers to a specific quality of light: uniform, warm, non-spectral, and non-patterned.

Gold is the colour of coherence. It is light without fragmentation, without geometry, without fluctuation. In contemporary phenomenological language, this corresponds to the collapse of structured visual form into pure light. The work of form is complete. But…you have to experience yourself how the golden light flows. If you do slow yoga and keep the eyes closed, the light will come in waves. Not only golden, but also in purple and green. You will see in move. Just watch. You will come to understand the many transformations of the light.

Comprehending the Incomprehensible

Kabir then states that one who reaches this stage “comprehends the incomprehensible.” This is not conceptual understanding. Kabir relentlessly mocks conceptual theology elsewhere. What he points to here is noetic certainty: knowing without representation, clarity without explanation. Just watching and recognizing you are experiencing the essence of your consciousness expressed as light. In the chapters on the Yoga of the inner light we have talked about this in more detail.

This is knowledge by presence, based on self-rembering.

The Mind’s Abode in Heaven

Finally, Kabir says that the mind “makes its abode in heaven.” Heaven here is not a cosmological location. It is a mode of abiding. The restless oscillation of the mind ceases. Awareness rests in light, not as observer, but as participant. The the watcher and the watched melt into one experience. It is nothing mystical. It is the essence of our own awareness.

From the perspective of the Yoga of the Inner Light, this marks the transition from perceiving light as content to recognizing it as the condition of perception itself.

Kabir as a Teacher of Inner Light

Read in this way, the Chauntīsī passage functions as a concise map of inner luminous development. Kabir does not present doctrine, metaphysics, or cosmology. He presents a path of seeing.

This makes Kabir a crucial historical witness for the rediscovery of the Yoga of the Inner Light. Long before later systems formalized inner light into hierarchies or mythic worlds, Kabir spoke directly from experience. He instructed his listeners not to believe, not to imagine, but to experience. That is why Kabir is one of the fouders of the fundaments of the Yoga of the Inner Light!

Shunyam Adhibhu