Through Another Man’s Eyes: Why John Dee Needed Edward Kelley’s Visions?

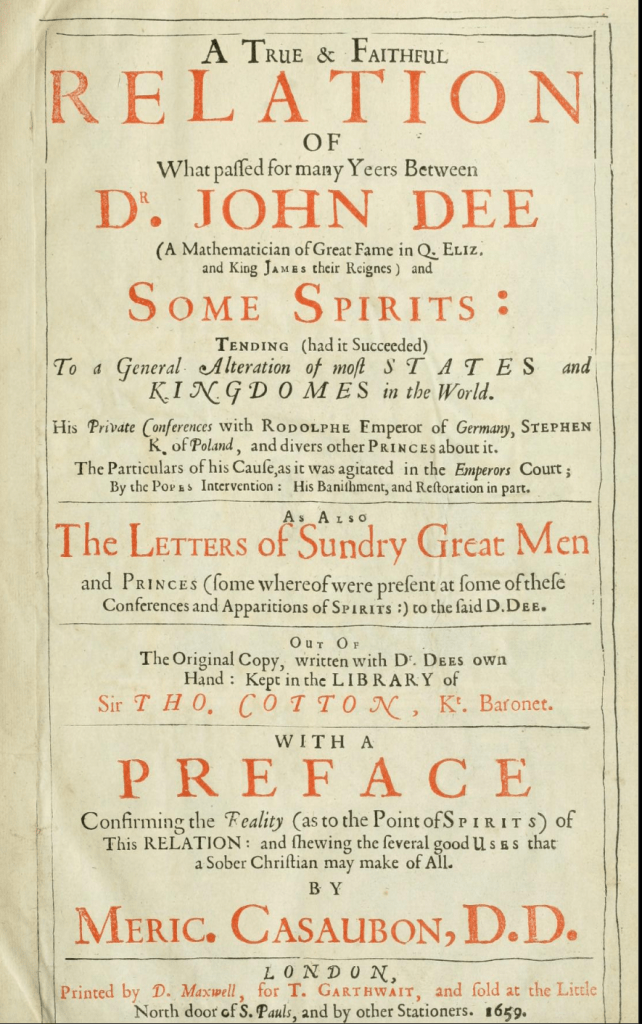

When we imagine John Dee (1527–1609), the legendary Elizabethan scholar and court magician, we often picture him staring into a black obsidian mirror, calling forth visions of angels. Yet Dee himself rarely gazed into the mirror. Instead, he worked through an intermediary, a “scryer,” who would describe the images and messages that appeared within the dark, reflective surface. His most famous scryer was Edward Kelley (1555–1597), whose dramatic visions laid the foundation of the Enochian magical system.

Why did Dee, who was so devoted to his mystical pursuits, not simply do the scrying himself? The answer lies in tradition, temperament, and practical considerations.

In 1580, Dee began experimenting with evocation and scrying in an effort to contact and communicate with angels. He initially sought the assistance of a “scryer” to act as an intermediary between himself and the spiritual realm. His early attempts with various scryers were disappointing, but in 1582 he encountered Edward Kelley, whose remarkable abilities deeply impressed him. Dee soon took Kelley into his service and dedicated himself fully to these supernatural explorations.

The Tradition of the Magus and the Seer

In Renaissance ceremonial magic, the roles of the operator (magus) and the seer (scryer) were often deliberately separated. The operator prepared the ritual space, performed invocations, and directed the session, while the scryer entered a receptive state to perceive spiritual beings or messages. This separation was believed to preserve the purity of the vision, preventing the operator’s strong will or intellect from interfering with what appeared.

Dee, as a learned magus, saw himself as the orchestrator of the ritual. His role was to invoke, to question, and to record. By delegating the visionary work to Kelley, Dee could maintain focus on the intellectual and spiritual framework, ensuring that the visions were faithfully documented without distortion.

An Analytical Mind Versus a Visionary Gift

Dee was a mathematician, geographer, and philosopher, an intensely analytical thinker. This intellectual disposition made him a brilliant planner and chronicler, but not necessarily the best candidate for deep trance or spontaneous visionary experiences. The kind of surrender required for mirror-gazing can be difficult for a mind trained to calculate and analyze.

Kelley, by contrast, had a vivid imagination and a willingness to enter altered states of consciousness. Dee came to believe that Kelley had a rare “gift” for perceiving angels and spiritual beings. The magus would guide the session by asking questions and interpreting what Kelley reported, while Kelley’s mind roamed freely within the visions of the mirror.

The Practicality of Recording

The scrying sessions often produced long and complex messages. Many included mysterious sigils, tables of letters, or words in what Dee and Kelley believed to be an angelic language. Recording these accurately was crucial to Dee’s project. By not scrying himself, Dee could concentrate on writing down the dialogues, ensuring nothing was lost.

Imagine trying to gaze into a mirror, receive a vision, interpret it, and simultaneously take detailed notes. For Dee, this division of labor was not just traditional but practical. Kelley would describe what he saw—sometimes dictating entire passages—while Dee meticulously transcribed every detail in his diaries.

John Dee’s sessions with Edward Kelley, as recorded in the manuscript Sloane 3191 (later compiled as De Heptarchia Mystica), show how he sought to communicate with the angels governing the seven planetary spheres.

His aim was nothing less than to uncover divine mysteries and restore the lost harmony between man and God.

In these sessions, Kelley would gaze into the obsidian mirror or a crystal, describing in detail the angelic beings that appeared. Dee carefully transcribed these accounts, adding diagrams and drawings to record what he believed to be their gestures, attire, and symbols of power.

For example, Dee writes of King Carmara appearing “in a long purple robe,” surrounded by seven princely attendants. Other angels, such as Hagonel, manifested with 42 ministers, represented in the manuscript as seven rows of six dots, and were seen tossing golden balls that dissolved into hollow bladders upon closer inspection.

Prince Bornogo’s ministers performed magical feats, vanishing like drops of water or cascading like hailstones, and even arranged themselves into lettered formations that Dee meticulously illustrated.

These elaborate visions reflect Dee’s belief in the sacred significance of the number seven and his conviction that he was witnessing a structured, divine language communicated through celestial beings.

Objectivity and Validation

There may have also been a psychological reason. If Dee had been both the seer and the recorder, he might have doubted whether the visions were merely projections of his own mind. By working through Kelley, there was a sense of objectivity, another witness to the phenomena. Kelley’s independent descriptions of angelic beings, letters, and messages gave Dee confidence that he was accessing a genuine spiritual realm.

Early Attempts and Kelley’s Arrival

Before Kelley, Dee experimented with other scryers, but none impressed him. His early attempts were either unproductive or filled with visions that Dee considered unreliable. This changed in 1582 when he met Kelley. Kelley’s immediate ability to “see” in the mirror amazed Dee. The two formed a partnership, and Dee devoted much of the next years to recording Kelley’s reports.

This collaboration produced a vast body of material, including the now-famous Enochian language, which Dee believed was a direct angelic communication. None of this would have been possible without Kelley’s willingness to serve as a visionary medium.

The Black Mirror as a Collaborative Space

For Dee, the black mirror was not a personal instrument of mystical introspection but a stage for dialogue. It was the meeting point of intellect and vision, a tool that allowed the magus and the scryer to explore the unseen together. Dee’s brilliance lay not in seeing visions himself but in structuring, guiding, and interpreting them. He was the architect, while Kelley acted as the messenger.

In this sense, Dee’s choice not to scry was not a weakness but a strength. It allowed him to focus on the larger framework of his spiritual project, a project that combined theology, science, and magic into a unified quest for divine wisdom.

The Holy Table

Central to Dee’s heptarchic rituals was the “Holy Table,” also called the “Table of Practice,” an altar-like structure that served as the focal point of his angelic work. The intricate design of this table, featuring symbolic inscriptions and geometric patterns, is believed to have been inspired by earlier magical diagrams known as the almandal or Semephoras tables.

Dee encountered these in a grimoire by Berengar Ganell, written in 1346 and titled Summa Sacre Magice (or “Compendium of Sacred Magic”). This compendium profoundly shaped Dee’s methods, particularly through its detailed chapter on the Sigillum Dei Aemeth, or “Sigil of God,” which Dee employed as a powerful amulet to facilitate communication with the angelic hierarchy.

Dee’s own annotated copy of Ganell’s work, filled with notes and reflections, is preserved today at the Universitätsbibliothek Kassel, a testament to the influence of medieval magical thought on his visionary experiments.

Conclusion

John Dee’s work with Edward Kelley remains one of the most fascinating chapters in the history of Western esotericism. His decision not to scry himself reflects the complexity of his character: a man who balanced rational intellect with deep mystical longing. For Dee, the black mirror was not about personal visions, but about unlocking the hidden structures of reality, with Kelley’s eyes as the lens and Dee’s mind as the interpreter. The Black Mirror remains a tool we can use! Read my recent article hereunder for more content!

Keppel Hesselink JM (2025). The Ancient Art of the Black Mirror and the Science of Inner Vision. PsyArXiv Preprints https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/fwb7v_v1

Shunyam Adhibhu