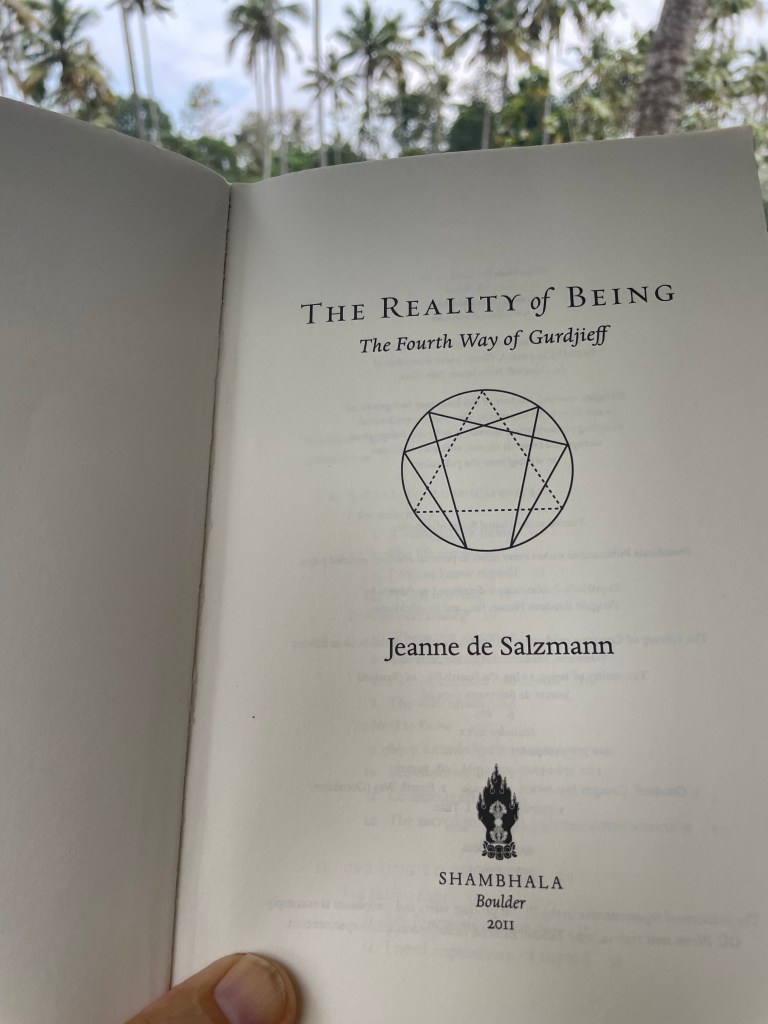

The Reality of Being, entering the work of Gurdjieff

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (c. 1866, 1949) is one of the most important and at the same time most misunderstood spiritual masters of the twentieth century. Like Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895, 1986) and Osho (1931, 1990), he addressed the fundamental question of human consciousness and unconsciousness. Yet his approach differs markedly from theirs, both in tone and in origin. However,all 3 masters agreed upon one thing: as humans we can evolveinto beings which are present and awake. ALtgought their methods differ, the aim is always the same.

But..

Where Krishnamurti spoke from radical negation and insight, and Osho from ecstatic synthesis and existential rebellion, Gurdjieff worked from a body of practical knowledge rooted in ancient traditions.

His sources were not primarily philosophical or devotional, but initiatory and experiential. During his early travels through Central Asia, the Middle East, Egypt, Anatolia, and the Caucasus, he encountered fragments of esoteric knowledge preserved in Sufi brotherhoods, early Christian Gnosticism, and ancient ritual practices. These traditions, in his view, did not aim at belief or moral improvement, but at the conscious transformation of the human being.

Gurdjieff described the ordinary human condition as one of waking sleep, a state in which thoughts, emotions, and actions arise mechanically. Like a zombie. Liberation, he insisted, does not come through ideas alone, nor through withdrawal from life, but through sustained inner work carried out in the midst of ordinary existence. This became known as the Fourth Way, a path that integrates body, feeling, and mind simultaneously. And leads to a state of awake illumination.

Jeanne de Salzmann and the continuity of the work

Jeanne de Salzmann (1889, 1990) was Gurdjieff’s closest collaborator and the primary guardian of his work after his death. Trained as a musician and deeply sensitive to inner perception, she understood that Gurdjieff’s teaching could easily be reduced to theory if it lost its experiential grounding.

For decades after 1949, Jeanne de Salzmann worked quietly with groups across Europe and the United States, emphasizing direct sensation, divided attention, and the role of the body and breath as anchors of presence. She gradually shifted the emphasis of the work from understanding ideas to living states, from explanation to verification. This makes her book so valuable. And it is the reason we go into this book more deeply.

Why The Reality of Being was written

The Reality of Being was compiled from Jeanne de Salzmann’s notebooks late in her life. It is not a systematic teaching manual, nor a personal memoir in the usual sense. It is a record of inner observation, written out of concern that Gurdjieff’s work might survive in form but lose its inner substance.

The book returns again and again to essential questions. What does it mean to be present in the body? It closely resembles our emphasis on breath. What role does breath play in unifying inner and outer attention? How does a deeper sense of “I” emerge beyond personality and habit? These are not abstract inquiries. They are practical and immediate, meant to be tested in lived experience.

Why this book matters NOW?

In a time when spiritual practice is often reduced to techniques for relaxation or self-improvement, The Reality of Being offers a different orientation. It does not promise comfort. It invites sincerity. It does not aim at escape. It points toward embodiment.

For Breath4Balance, a series of blogs on this book is not about preserving a tradition but about engaging a living question. What does it mean to be here, now, in breath, sensation, and attention, without adding anything and without turning away.

This series will explore the text slowly, experientially, and without dogma, allowing it to function as what it truly is, an invitation to observe, to sense, and to be.

In the final years of his life, George Ivanovich Gurdjieff gave Jeanne de Salzmann a set of instructions that were both simple and demanding. He asked her to safeguard the essence of the work, not its outer forms, and to continue it without compromise, without personal authority, and without dilution. Most importantly, he emphasized that the work must remain rooted in direct experience, in the sensation of the body, in breath, and in conscious presence, rather than in explanation or belief. Jeanne de Salzmann took this responsibility with extraordinary seriousness. She did not seek visibility, nor did she attempt to systematize the teaching into something easily consumable. Instead, she embodied it. The fact that she lived to the age of 101 is often mentioned not as a curiosity, but as a quiet confirmation of the depth and integrity with which she lived the work, fully engaged with life, attentive to the inner demands of presence, until the very end.

Longevity, presence, and embodied attention

Jeanne de Salzmann (1889, 1990) lived to the age of 101. This fact is sometimes mentioned with mild amazement but rarely explored in depth. Within the context of her life and work, longevity appears less as a biological accident and more as a natural consequence of how attention, breath, and body were lived from within.

Jeanne de Salzmann did not pursue health as a goal. She did not promote techniques for vitality or longevity. Instead, her life was oriented toward presence, a continuous effort to inhabit the body consciously, to sense rather than imagine, and to remain in contact with breath as a living bridge between inner and outer worlds. This quality of attention does not accumulate tension. It does not fragment experience. It organizes life from inside.

In modern culture, aging is often framed as decline, something to be resisted or delayed. In contrast, Jeanne de Salzmann’s life suggests another possibility, that sustained inner coherence reduces inner friction. When attention is divided yet unified, when breath is not forced but received, and when the body is inhabited rather than used, energy is conserved rather than scattered.

Embodied attention is not dramatic. It does not announce itself. It is quiet, steady, and economical. Over decades, this quality may matter more than any intervention. Presence reduces unnecessary effort. Sensation replaces mental strain. Breath regulates without control. In this sense, longevity is not something added to life, it is something that emerges when life is not continuously leaking energy through unconscious tension.