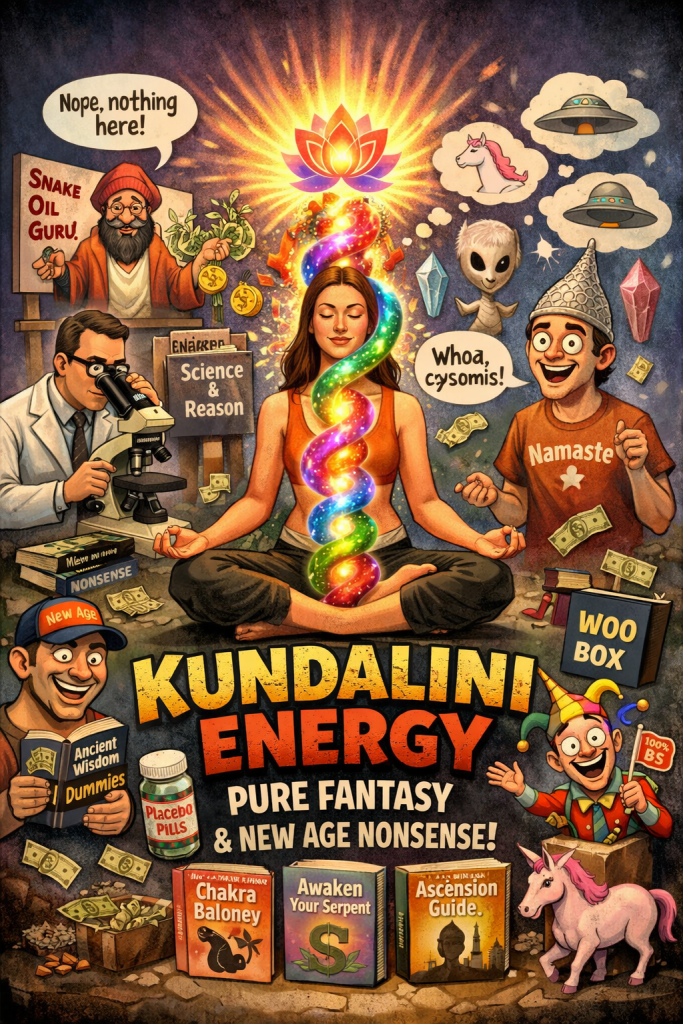

All crazy stories on Kundalini Awakening, very popular in the New Age. All lies and fantasies. Here’s why that is!

In modern global spirituality, kundalini has come to occupy a position of near-mythic centrality. Workshops promise awakening of dormant serpent energy; books describe dramatic ascents through chakras; practitioners seek explosive experiences at the base of the spine. Yet historically, kundalini was not the foundational axis of yoga. A careful examination of classical sources reveals that the essence of yoga lies elsewhere.

The earliest systematic formulation of yoga philosophy appears in the Yoga Sutras attributed to Patañjali, likely compiled between the second century BCE and fourth century CE. The central definition is famously concise: yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ — yoga is the cessation of fluctuations of the mind. The entire structure of classical yoga unfolds from this premise. Ethical discipline, posture, breath regulation, sense withdrawal, concentration, meditation, and samadhi serve a single purpose: stabilization and purification of awareness.

There is no mention of kundalini in the Yoga Sutras. No serpent coiled at the base of the spine. No ascending energy drama. Liberation is achieved not by stimulating a latent force but by discriminative knowledge (viveka-khyāti) separating pure awareness (puruṣa) from the fluctuations of nature, being our jumping thoughts (prakṛti).

Similarly, the Bhagavad Gītā emphasizes disciplined action, devotion, and insight. It discusses prana and meditative states but does not construct a metaphysics of serpent ascent. Early Upanishadic literature describes the subtle body in various ways, yet the elaborate chakra-kundalini system as popularly known today appears primarily in later Tantric and Hatha yoga texts.

The medieval period, particularly from the 12th to 15th centuries, produced manuals such as the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā, the Śiva Saṃhitā, and the Sat-Cakra-Nirūpaṇa. These works describe subtle channels (nāḍīs), energy centers (cakras), and a coiled force termed kundalini. In these texts, kundalini functions within a structured psycho-energetic map. However, even here, the aim is not spectacle but transformation of consciousness culminating in samadhi. The serpent imagery is symbolic and embedded in a broader discipline of breath control, bodily locks (bandhas), and meditative absorption.

The modern elevation of kundalini into the defining feature of yoga owes much to 19th and 20th century reinterpretations. Colonial-era translations, Theosophical reinterpretations, and global esoteric movements reframed Tantric symbolism within Western occult frameworks. Sir John Woodroffe (Arthur Avalon) popularized chakra diagrams in English-language scholarship. Later figures systematized “Kundalini Yoga” as a branded spiritual path, often detached from its historical complexity.

Within Indian traditions themselves, the role of kundalini has always been more nuanced. Advaita Vedanta centers on self-inquiry and non-dual realization. Bhakti traditions emphasize devotion and surrender. Sikh teachings refer to internal awakening but often reinterpret serpent imagery metaphorically. In several streams, the emphasis remains clarity of awareness rather than energetic dramatization.

A particularly striking critique of kundalini imagery appears in the teachings of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866–1949), transmitted through his student P. D. Ouspensky. Gurdjieff spoke not of “kundalini” but of “kundalina,” a force he described as a kind of artificial or hypnotic energy implanted in humanity. According to his teaching, this force distorts perception and sustains illusion. Rather than awakening a divine serpent, human beings must awaken from mechanical sleep.

Gurdjieff’s interpretation does not align philologically with classical Indian texts; it is a psychological allegory rather than a historical reconstruction. Yet it offers a powerful warning. For Gurdjieff, imagination can masquerade as transformation. Emotional intensity, bodily sensations, and visionary states may create the illusion of awakening while leaving fundamental patterns unchanged. What he termed “kundalina” represents the inertia of conditioned consciousness, not its liberation.

The relevance of this critique lies in its emphasis on sobriety. Spiritual traditions across cultures caution against fascination with extraordinary states. In Buddhist meditation manuals, practitioners are warned not to cling to lights or visions. In Christian mysticism, extraordinary experiences are considered secondary to humility and love. Meister Eckhart insisted that attachment to experiences obstructs the birth of God in the soul.

When kundalini becomes the focal point of spiritual pursuit, the risk is displacement. Energy becomes the object; liberation recedes. Historically, yoga aimed at stabilization of awareness, ethical purification, and insight into the nature of mind. Whether described as ascent or descent, the essential transformation is cognitive and existential.

The metaphor of ascent itself is not universal. Many traditions describe illumination as the descent of grace rather than upward striving. In Christian theology, divine initiative precedes human effort. In certain yogic streams, prana is understood as flowing from subtler to grosser levels, not merely rising from below. The directionality of spiritual transformation is symbolic, not anatomical.

Modern neuroscience adds another layer to this discussion. Practices involving breath retention, focused attention, and bodily locks undoubtedly affect autonomic regulation and cortical networks. Alterations in the Default Mode Network correlate with diminished self-referential processing. These findings illuminate how disciplined practice reshapes brain dynamics. Yet none of this requires literalizing serpent energy.

The enduring essence of yoga, viewed historically, is disciplined integration. Body, breath, mind, and awareness are harmonized. The practitioner learns to observe thoughts without identification, to stabilize attention, and to cultivate insight. Extraordinary sensations may arise, but they are byproducts, not the telos.

Cultural traditions degrade when symbols are mistaken for substance. When yoga becomes mere physical exercise, its contemplative depth is lost. When it becomes energetic sensationalism, its discriminative clarity dissolves. Classical texts consistently subordinate phenomena to realization. Fantasies are never healthy. But Oh man, so many people fantasize over Kundalini, or worse, give courses in Kundalini awakening. Money talks.

Kundalini, in its historical context, is one symbolic articulation of transformative potential. It is not the universal core of yoga. The central axis remains freedom from ignorance, whether that ignorance is described as misidentification with prakṛti, as avidyā, or as mechanical sleep.

Gurdjieff’s sharp warning, though arising outside the Indian tradition, echoes an ancient insight: imagination can entangle as easily as it can inspire. Genuine transformation demands sustained attention, ethical grounding, and inner discipline. The serpent may symbolize latent power, but power without clarity leads nowhere.

The essence of yoga, then, is not the awakening of a coiled force but the awakening from illusion. Across centuries and traditions, the aim remains consistent: stabilization of consciousness, dissolution of misidentification, and realization of a deeper order of awareness. Kundalini can be understood as metaphor, method, or myth. What cannot be abandoned is the sober work of awakening. Just stay with your own experiences and do not copy the shit of other’s people illusions.